Abstract

This paper proposes that the Seven Element Structure (7ES)—comprising Input, Output, Processing, Controls, Feedback, Interface, and Environment—is not merely an analytical model but a fundamental, recursive architectural pattern inherent to all functional systems. We hypothesize that this framework describes a universal organizational principle that manifests fractally from quantum fields to cosmic structures. While these elements are individually well-established in systems theory, their synthesis into this specific, minimal, and recursive set represents a novel ontological claim about the nature of system-ness itself. We present evidence of the framework’s applicability across more than 60 + orders of magnitude in spatial scale, from the Planck scale to the cosmic web and propose a formal research program to validate or falsify the claim that these seven elements constitute the necessary and sufficient functional architecture for any coherent system. Validation of this hypothesis would have profound implications for cross-disciplinary collaboration, system design, and our fundamental understanding of a structured reality.

1. Introduction: The Fragmentation Problem in Systems Theory

Systems Theory has provided invaluable insights into complex phenomena across biology, economics, engineering, and social sciences since its emergence in the mid-twentieth century. Foundational work by Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Norbert Wiener, Claude Shannon, and W. Ross Ashby established core principles that guide our understanding of feedback loops, adaptation, emergence, and control mechanisms within diverse systems.

However, despite its broad applicability and theoretical sophistication, contemporary systems theory lacks a standardized structural framework that can be universally applied across disciplines and scales. The conceptual elements within systems theory remain fragmented across different theoretical traditions. Shannon emphasized information transmission and communication channels. Wiener focused on feedback and control in cybernetic systems. Bertalanffy stressed open system exchanges with environments. Ashby explored variety and requisite complexity in regulatory mechanisms. While each contribution has proven valuable within its domain, no widely adopted framework integrates these insights into a single, functionally complete structure.

This fragmentation creates practical challenges. Researchers in different fields often speak past one another, using different terminologies for functionally similar concepts. Engineers designing technological systems, biologists studying ecosystems, economists modeling markets, and sociologists analyzing institutions all work with systems, yet lack a common analytical language. The absence of a unified framework limits cross-disciplinary collaboration and obscures structural similarities that could inform more effective system design and intervention.

The 7ES Framework addresses this gap by synthesizing existing systems theory concepts into seven fundamental elements that collectively describe any operational system. This synthesis is not an invention of new theoretical primitives but rather a careful aggregation and formalization of established concepts into a complete, memorable, and operationalizable structure. The framework’s claim to universality—that all functional systems necessarily contain all seven elements—invites rigorous empirical testing and theoretical scrutiny.

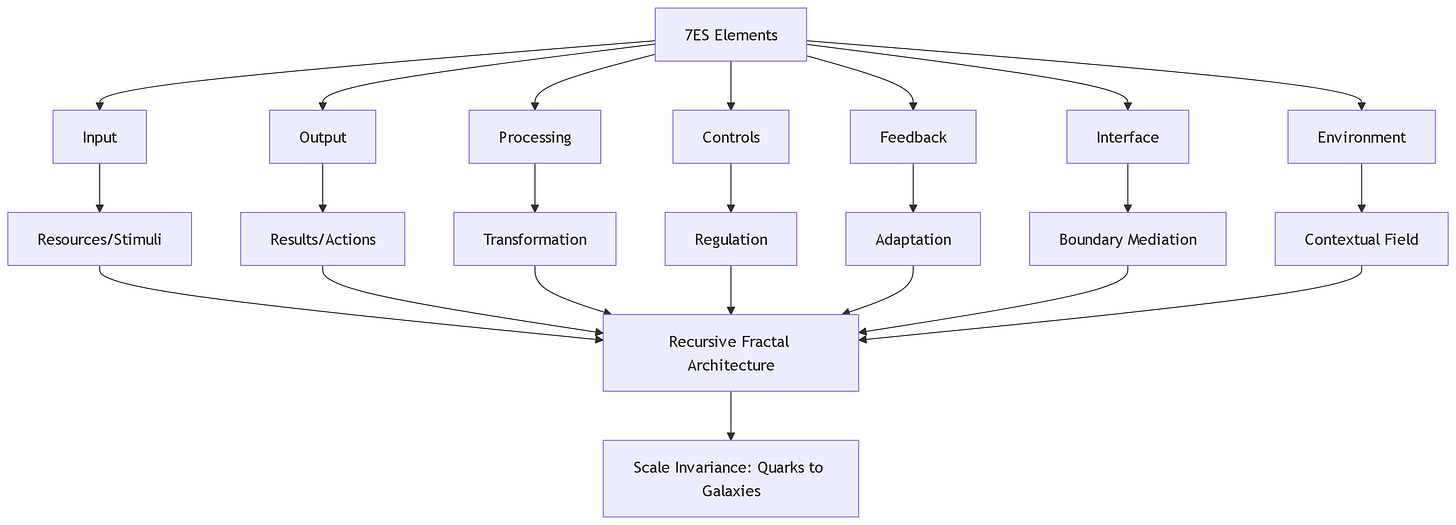

2. The Seven Element Structure Framework

The 7ES Framework proposes that every functional system can be comprehensively analyzed through seven fundamental elements. Each element represents a necessary function without which system operation either fails or fundamentally changes character.

2.1 Element Definitions

Input refers to resources, signals, energy, or information that enter a system from its environment, initiating or modifying internal processes. Inputs provide the raw materials or stimuli that enable system function. In biological systems, inputs include nutrients and oxygen. In economic systems, inputs comprise capital, labor, and raw materials. In quantum field systems, inputs consist of particles and energy states entering interaction domains.

Output encompasses the results, products, actions, or signals that a system generates and transmits to its environment or to other systems. Outputs may be tangible products, behavioral actions, information flows, or state transformations. A photosynthetic organism outputs oxygen and glucose. An industrial facility outputs manufactured goods. The Higgs field outputs mass properties to elementary particles. Outputs often become inputs for other systems, creating cascading relationships across scales.

Processing involves the transformation or manipulation of inputs within a system to produce outputs. This includes metabolic pathways in biological systems, computational algorithms in digital systems, gravitational dynamics in astrophysical systems, and decision-making processes in organizational systems. Processing represents the core operational mechanism through which systems create value, transform energy, or generate information.

Controls are mechanisms within a system that guide, regulate, or constrain behavior to achieve desired outcomes or maintain operational parameters. Controls may be internal governance mechanisms or external regulatory constraints. In engineered systems, controls include thermostats, governors, and algorithmic constraints. In natural systems, controls manifest as physical laws, conservation principles, and boundary conditions. Controls differ from feedback in temporal orientation—controls are proactive constraints embedded in system design, whereas feedback is reactive information derived from outcomes.

Feedback is the existential or operational state of a system that confirms, regulates, or challenges its coherence and viability. It is the necessary information about a system’s relationship with its own operational constraints. This definition represents a critical refinement of the classical cybernetic concept, expanding it to encompass two distinct modes:

Active (Dynamic) Feedback: An explicit signal or data loop used for correction or amplification (e.g., a thermostat reading, proprioception, a financial report).

Passive (Implicit) Feedback: The mere persistence of the system’s structure and function, which serves as a continuous confirmation that its processes are within viable parameters. In this view, the system’s continued existence is the feedback. For example, the stable existence of a proton, the fixed binding of a crystal, or the persistent vacuum state of the Higgs field all constitute passive feedback that their internal and external conditions remain coherent.

This distinction is essential for applying the framework universally, as it allows the identification of feedback in non-cybernetic systems—such as fundamental physical fields, static structures, or simple stable entities—where no explicit signaling loop is present. The presence of either active or passive feedback is a necessary indicator of a system’s functional status.

Interface defines the boundaries, touchpoints, or interaction modalities between a system and its environment or between subsystems within a larger system. Interfaces mediate exchanges, enforce compatibility standards, and determine whether interaction is possible across system types. In biological systems, cell membranes serve as interfaces. In digital systems, Application Programming Interfaces enable communication between software components. In social systems, communication channels and institutional platforms function as interfaces. Interfaces exist at every scale, from molecular binding sites to cosmic horizons.

Environment encompasses all external conditions, systems, and contexts that interact with or influence the system under analysis. The environment provides resources, constraints, perturbations, and opportunities for system evolution. For a cell, the environment includes surrounding tissue and chemical gradients. For a corporation, the environment includes market conditions, regulatory frameworks, and technological landscapes. For cosmic structure, the environment includes unobservable regions beyond the cosmic horizon and the temporal context of cosmic evolution.

3. The Recursive Property and Fractal Structure

A distinguishing feature of the 7ES Framework is its recursive property. Each of the seven elements can itself be understood as a subsystem governed by the same seven-element structure. This creates a fractal hierarchy enabling analysis at any chosen level of granularity.

Consider the Processing element in a manufacturing system. Processing involves the transformation of raw materials into finished products. Within this processing function, we can identify inputs to the processing subsystem (raw materials entering the factory floor), outputs from processing (intermediate products moving to assembly), processing within processing (specific machine operations), controls governing processing (quality standards and machine settings), feedback within processing (sensor data monitoring production rates), interfaces of processing (conveyor systems and robotic arms), and the environment of processing (factory conditions such as temperature and humidity).

This recursive structure enables continuous auditability across scales. An electron’s energy state, which is an output of quantum mechanical processes, becomes an input to atomic bonding. Atomic bonding outputs become inputs to molecular formation. Molecular structures become inputs to cellular processes. Cellular outputs become inputs to tissue function. This cascading relationship continues through organism behavior, ecological interactions, and planetary biogeochemical cycles.

The recursive property has profound implications. It suggests that systems theory describes not merely useful analytical categories but fundamental structural properties that manifest at every level of organization. It provides a mechanism for understanding how micro-level interactions generate macro-level patterns and how macro-level contexts constrain micro-level possibilities. The fractal nature of 7ES enables researchers to zoom in or out across scales while maintaining analytical coherence.

4. Evidence of Universality Across Scales and Domains

The claim that all functional systems contain all seven elements requires empirical demonstration across diverse cases. The framework’s applicability is tested across the entirety of the observable scale of the universe. From the Planck Length (ℓ_P ≈ 1.6 × 10⁻³⁵ m), the smallest meaningful scale in physics, to the diameter of the observable universe (≈ 8.8 × 10²⁶ m), spans a range of approximately 62 orders of magnitude. The consistent identification of all seven elements across this range provides compelling preliminary evidence for the pattern’s fundamentality.

4.1 Quantum Scale: The Higgs Field

The Higgs field represents one of the most fundamental systems in physics, providing mass to elementary particles through field interactions. At this scale, inputs consist of particles with specific quantum numbers entering the field’s interaction domain. Outputs include mass acquisition proportional to coupling strength and observable particle trajectories. Processing occurs through Yukawa coupling mechanisms and spontaneous symmetry breaking, transforming massless quantum excitations into massive particles. Controls include coupling constants that determine interaction strength for each particle type, conservation laws constraining interactions, and the vacuum expectation value regulating mass scales.

Feedback in the Higgs field provides a quintessential example of Passive (Implicit) Feedback. The field’s continued, stable existence throughout the universe at its non-zero vacuum expectation value is not an explicit signal, but a continuous, implicit confirmation that its operational parameters are met. The mere persistence of this field configuration—and by extension, the stable masses of elementary particles and the structure of the vacuum itself—is the feedback. It confirms the coherence of the field with its environmental constraints (the laws of the Standard Model, the cosmological context). Should this state become unstable, the resulting phase transition would represent a catastrophic failure of this passive feedback loop. Alongside this fundamental passive feedback, Active (Dynamic) Feedback also operates through quantum corrections and self-coupling in the field equations, where the field’s own configuration dynamically influences its future state.

The interface exists at interaction vertices where particles couple to the field and at energy thresholds determining when field excitations become observable Higgs bosons. The environment encompasses other quantum fields, spacetime geometry, and cosmological evolution parameters that influence field behavior.

4.2 Biological Scale: Cellular Metabolism

A single cell provides a clear example of 7ES structure in living systems. Inputs include nutrients, oxygen, and chemical signals from the extracellular environment. Outputs comprise metabolic waste products, proteins synthesized for cellular functions, and signaling molecules sent to other cells. Processing involves complex biochemical pathways including glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and oxidative phosphorylation that transform nutrients into usable energy and cellular building blocks.

Controls in cellular systems include gene regulatory networks that determine which proteins are expressed, enzyme concentrations that govern reaction rates, and physical constraints such as membrane permeability. Feedback mechanisms are extensive, ranging from allosteric regulation where enzyme products inhibit enzyme activity, to hormonal signaling cascades that adjust metabolic rates based on organismal needs, to apoptosis pathways that trigger programmed cell death when damage exceeds repair capacity. The cell membrane serves as the primary interface, selectively permitting molecular transport and receiving extracellular signals through receptor proteins. The environment includes surrounding tissue, blood supply providing nutrients and removing wastes, temperature and pH conditions, and mechanical forces acting on the cell.

4.3 Social Scale: Racism as a Systemic Structure

Analyzing racism through the 7ES Framework reveals how abstract ideological systems exhibit the same fundamental structure as physical systems. Inputs to the system of racism include cultural narratives transmitted across generations, media representations reinforcing stereotypes, economic anxiety seeking explanatory frameworks, and historical trauma embedded in collective memory. Outputs manifest as discriminatory behaviors in interpersonal interactions, institutional policies creating disparate impacts, resource allocation patterns perpetuating inequality, and intergenerational transmission of advantage and disadvantage.

Processing involves cognitive mechanisms including stereotype formation, in-group versus out-group categorization, confirmation bias, and rationalization strategies that maintain belief consistency despite contradictory evidence. Controls include legal structures that either enforce or prevent discriminatory practices, social norms determining acceptable behavior, institutional policies governing resource distribution, and power structures determining whose perspectives dominate public discourse.

Feedback operates through multiple channels. Confirmation bias creates reinforcing feedback where individuals seek information supporting existing beliefs while dismissing contradictory evidence. Disparate outcomes resulting from discriminatory policies feed back into justification narratives, creating self-fulfilling prophecies. Resistance movements and civil rights advocacy provide corrective feedback challenging system assumptions. Intergenerational trauma perpetuates the system by creating psychological and material conditions that reinforce racial divisions.

The interface of racism appears wherever ideology meets lived reality—in social interactions shaped by racial expectations, in educational institutions transmitting historical narratives, in legal encounters where enforcement patterns differ by race, and in media platforms that shape public perception. The environment includes historical contexts such as slavery and colonialism that established initial conditions, economic systems determining resource distribution, political climates affecting policy possibilities, and demographic shifts changing population composition.

The persistence of racism despite moral condemnation demonstrates a key insight—the system persists because all seven elements remain functional and mutually reinforcing. Effective intervention requires addressing all seven elements simultaneously rather than focusing exclusively on individual attitudes or isolated policy changes.

4.4 Cosmic Scale: The Large-Scale Structure of the Universe

At the upper bound of observable scales, the cosmic web consists of galaxy superclusters, filaments, walls, and voids spanning billions of light-years. This structure tests whether 7ES applies beyond human-scale systems to the largest known organization in nature.

Inputs to cosmic structure include initial density fluctuations from quantum fluctuations during cosmic inflation, dark matter providing gravitational scaffolding, baryonic matter flowing along dark matter filaments, and dark energy driving accelerated expansion. Outputs comprise galaxy clusters forming at filament intersections, gravitational lensing effects bending light across cosmic distances, void expansion as matter evacuates underdense regions, and the cosmic web geometry itself as an emergent pattern.

Processing involves gravitational collapse along lines of dark matter overdensity, hierarchical structure formation where small structures merge into larger ones, gas cooling and heating within filaments, and N-body gravitational dynamics among trillions of interacting masses. Controls include fundamental physical constants such as the gravitational constant and speed of light, cosmological parameters determining matter and dark energy densities, conservation laws governing energy and momentum, general relativity equations governing spacetime curvature, and the initial power spectrum of density fluctuations from inflation.

Feedback at cosmic scales operates through gravitational self-interaction. Overdense regions attract additional matter, increasing density and gravitational attraction in a positive feedback loop that creates filamentary structure. Underdense regions lose matter to surrounding overdensities, decreasing density and further accelerating evacuation in a complementary positive feedback loop creating voids. The competition between gravitational collapse and cosmic expansion provides continuous feedback about the balance between matter and dark energy. Structure formation rates signal which force dominates at different scales. Critically, the cosmic web’s continued coherent structure itself constitutes feedback confirming that gravitational dynamics dominate over expansion at filament scales.

Interfaces in cosmic structure include filament-void boundaries where matter density transitions sharply, virial radii of galaxy clusters marking boundaries between infalling and bound matter, the cosmic horizon beyond which light has not had time to reach observers, and temporal interfaces such as the recombination surface visible in cosmic microwave background radiation. The environment of the cosmic web includes regions beyond the observable horizon that are causally disconnected, earlier cosmic epochs providing initial conditions, and speculatively the multiverse or quantum vacuum substrate from which the universe emerged.

5. Theoretical Implications and Necessity Arguments

The consistency with which all seven elements appear across radically different system types and scales suggests that 7ES may describe not merely useful analytical categories but necessary structural features of systems themselves. This section examines the theoretical basis for claiming that these seven elements constitute necessary conditions for system function.

5.1 The Necessity of Feedback: Existence as Information Flow

Feedback initially appears to be the element most vulnerable to counterexamples, particularly in deterministic systems governed by fixed physical laws. However, a deeper analysis reveals feedback as logically entailed by system-ness itself.

A system is defined by coordinated interaction among its components. For interaction to remain coordinated, components must exist in mutually compatible states. Compatible states persist only if conditions enabling compatibility continue to be met. When conditions are met, this generates information—a signal—that enables continued operation. Information about state that influences continuation constitutes feedback by definition.

Consider the alternative. A purported system whose components interact without any state information would exhibit random, uncoordinated behavior. Such an arrangement would not constitute a system but rather a collection of independent elements. Therefore, system-ness entails feedback. This argument holds even for completely deterministic systems because deterministic continuation is predicated on current state, and state information flowing through the system to enable continuation is feedback.

Feedback need not involve adaptive learning, conscious monitoring, error correction, or time-delayed response loops. Feedback requires only that information about system state exists and influences system behavior. At the most fundamental level, a system’s continued operation is itself a feedback signal confirming functional compatibility of all elements. When a hurricane persists, that persistence confirms adequate energy input and favorable atmospheric conditions. When fusion continues in a stellar core, that continuation confirms sufficient pressure and temperature. When a cell maintains metabolism, that maintenance confirms nutrient availability and functional biochemical pathways. Conversely, system failure constitutes feedback signaling that critical conditions are no longer met.

A rock presents as a static object. However, as a coherent system (e.g., a silicate crystal structure), its Passive Feedback is its persistent chemical bonding resisting entropy. The moment it begins to erode or fracture, that is feedback that environmental conditions have exceeded its operational constraints. Its ‘processing’ is the ongoing electromagnetic forces maintaining its structure. To be a coherent system is to process, and to process is to generate feedback, even if only implicitly.

5.2 The Completeness Question: Why Seven?

The framework’s claim to provide a minimal, complete set of elements requires justification. Why these seven specifically, and not six or eight? Each element must be demonstrated as irreducible, and collectively they must be shown as sufficient.

Attempts to reduce the framework reveal why each element is necessary. Input and Output cannot be merged because systems require both resource acquisition and result generation, which serve distinct functions. Processing cannot be eliminated because transformation distinguishes dynamic systems from static arrangements. Controls and Feedback cannot be unified despite superficial similarity because they differ fundamentally in temporal orientation—controls are proactive constraints embedded in system design while feedback is reactive information derived from outcomes. Interface cannot be subsumed into Input and Output because boundary mediation serves a distinct function determining what can enter or exit and under what conditions. Environment cannot be eliminated because systems are defined partially by what they are not—the boundary between system and non-system is constitutive.

The sufficiency question asks whether an eighth element is required. Extensive testing across diverse systems has not revealed any functional aspect that cannot be categorized within one of the seven elements. Proposed candidates for additional elements typically prove to be either combinations of existing elements or emergent properties arising from element interaction rather than fundamental elements themselves. Purpose or intentionality, for example, is encoded in Controls and Processing that shape system behavior toward outcomes. Emergence is the result of element interaction rather than a separate element. Adaptation combines Feedback and Controls enabling system modification.

5.3 Implications for System Definition

If all functional systems contain all seven elements, this provides a rigorous definition of what constitutes a system. A system is an organized arrangement of components exhibiting input acquisition, output generation, internal processing, behavioral constraints, state information flow, boundary mediation, and environmental context. This definition distinguishes systems from random collections of objects and provides clear criteria for identifying system boundaries.

This understanding has practical implications. When analyzing complex phenomena, researchers can use element identification as a diagnostic tool. If one or more elements cannot be identified, either the purported system is not actually operational, the system boundaries have been drawn incorrectly, or the missing element exists but has not been recognized. This systematic approach reduces ambiguity in system analysis.

6. Challenges and Limitations

Academic rigor requires acknowledging challenges, limitations, and potential objections to the framework.

6.1 The Definitional Flexibility Problem

Critics may argue that the framework’s ability to identify all seven elements in diverse systems stems from overly flexible definitions rather than genuine universality. If elements can be defined broadly enough, any phenomenon can be forced into the framework regardless of whether meaningful insight results.

This objection has merit and requires careful response. The framework’s definitions must maintain sufficient specificity to be falsifiable while remaining general enough to apply across domains. The key test is whether element identification provides analytical value beyond post-hoc categorization. Does recognizing the seven elements reveal previously unnoticed relationships, enable predictive capacity, or guide more effective interventions? If the framework merely relabels known phenomena without generating new insights, its utility remains limited regardless of its universality.

6.2 The Environment Boundary Problem at Cosmic Scales

At the largest observable scales, the concept of environment becomes philosophically complex. For subsystems, the environment is clearly external context. For the cosmic web as a whole, what constitutes external context becomes ambiguous. Unobservable regions beyond the cosmic horizon exist spatially but are causally disconnected. Earlier cosmic epochs provide temporal context but no longer exist in conventional sense. The multiverse, if it exists, would provide environmental context, but its existence remains speculative.

This challenge suggests that the framework applies most naturally to bounded systems distinguishable from their surroundings rather than to totality itself. Whether reality-as-a-whole can be analyzed through 7ES or whether the framework requires modification at absolute scales remains an open theoretical question.

6.3 Nested Complexity and Analytical Tractability

Real-world systems exhibit deep nesting where subsystems contain sub-subsystems recursively. While the framework’s recursive property is theoretically elegant, applying it to analyze deeply nested systems creates practical complexity. At what level should analysis focus? How are boundaries determined between hierarchical levels? When do recursive decompositions cease providing useful insight?

These questions do not invalidate the framework but highlight that practical application requires methodological development beyond theoretical formulation. Users need guidance on determining appropriate analytical granularity and managing computational complexity in deeply nested systems.

6.4 Cultural and Epistemological Considerations

The framework emerges from Western scientific traditions emphasizing analytical decomposition and mechanistic understanding. Alternative epistemologies, particularly indigenous knowledge systems, often conceptualize reality as fundamentally relational and interconnected rather than composed of discrete functional elements. Some traditions view the separation between system and environment as artificial, emphasizing instead the inseparability of all phenomena.

Incorporating diverse epistemological perspectives enriches the framework by challenging assumptions about system boundaries and element independence. The environment element, in particular, may require reconceptualization not as external backdrop but as co-creator in system dynamics. Recognizing relational knowledge and stewardship as integral controls and feedback mechanisms opens possibilities for more holistic system understanding.

7. Proposed Research Program

Validating or falsifying the 7ES Framework’s universality claim requires systematic empirical investigation across multiple domains and theoretical analysis of necessity arguments. We propose a multi-phase research program engaging specialists across disciplines.

7.1 Phase One: Systematic Domain Testing

The first phase involves comprehensive testing across established scientific domains to determine whether all seven elements can be consistently identified in representative systems. This phase should include:

Physical Systems Testing: Apply the framework to systems across scales including elementary particle interactions, atomic and molecular structures, condensed matter phenomena, thermodynamic systems, fluid dynamics, electromagnetic systems, gravitational systems, and astrophysical structures. Document element identification for each case and note any systems where elements prove difficult to identify or appear absent.

Biological Systems Testing: Analyze systems ranging from molecular biology (protein folding, enzymatic reactions, gene regulation) through cellular biology (metabolism, signaling, division) and organismal biology (nervous systems, immune responses, developmental processes) to ecological systems (predator-prey dynamics, ecosystem succession, biogeochemical cycles). Special attention should be paid to systems exhibiting emergence and self-organization.

Technological Systems Testing: Examine engineered systems including mechanical devices, electrical circuits, computing systems, communication networks, manufacturing processes, transportation systems, and energy production and distribution systems. These human-designed systems provide cases where system architecture is explicitly known, enabling verification of element identification accuracy.

Social and Economic Systems Testing: Apply the framework to organizational structures, market systems, political institutions, communication networks, cultural systems, and ideological structures. These domains test whether the framework applies beyond physical and biological systems to abstract social constructions.

Mathematical and Computational Systems Testing: Investigate whether formal systems such as algorithms, logical systems, cellular automata, and abstract mathematical structures exhibit the seven elements. This extends the framework into purely informational domains.

For each domain, research should document successful element identification, cases where identification proves challenging, systems that appear to lack specific elements, and insights gained through framework application that were not obvious through domain-specific analytical approaches.

7.2 Phase Two: Falsification Attempts

Science advances through attempted falsification rather than confirmation alone. The second phase should actively seek counterexamples—systems that definitively lack one or more elements while still qualifying as functional systems.

Physical systems testing must explicitly include the extreme scales as the most stringent tests. Can a coherent 7ES structure be defined for a quantum fluctuation at the Planck scale? Can the universe-as-a-whole, at the largest scale, be meaningfully described without violating the definition of Environment? The framework stands or falls by its ability to consistently describe physics at these extremes.

Researchers should propose candidate counterexamples from their respective domains and analyze them rigorously. Does the system truly lack the proposed element, or has the element been overlooked or misidentified? If an element genuinely appears absent, does this indicate framework failure, or does it reveal that the candidate is not actually a functional system according to rigorous criteria?

This phase should particularly target edge cases including static systems with minimal dynamics, purely feedforward systems without apparent feedback loops, completely isolated systems without environmental interaction, systems at phase transitions or critical points, emergent phenomena that may transcend traditional system boundaries, and quantum systems where observation affects state.

Consciousness and Qualia: Does a subjective first-person experience constitute a system? If so, how are its Input (sensory data?), Processing (thought?), and Output (action/intent?) defined? The ‘Hard Problem of Consciousness’ represents a supreme test for any universal systems framework.

Mathematical Objects: Is the Mandelbrot set a system? Its breathtaking complexity emerges from a simple recursive function. Can its 7ES structure be meaningfully described?

Documentation should include detailed case studies of proposed counterexamples, analysis of whether elements are genuinely absent or merely difficult to identify, and discussion of implications for framework validity if genuine counterexamples are confirmed.

7.3 Phase Three: Comparative Framework Analysis

The 7ES Framework should be compared systematically with established systems theory frameworks to determine relative strengths, weaknesses, and appropriate application domains. Candidate frameworks for comparison include Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model, James Miller’s Living Systems Theory, the Input-Process-Output model common in information systems, Control Theory frameworks from engineering, Ecological Systems Theory, and various complexity science approaches.

Comparison should address questions including: Under what conditions does each framework provide superior analytical insight? Can 7ES identify system features that alternative frameworks miss? Do alternative frameworks reveal aspects that 7ES obscures? Can frameworks be integrated or translated between one another? What empirical predictions differ between frameworks, enabling experimental discrimination?

7.4 Phase Four: Methodological Development

If early phases confirm the framework’s broad applicability, subsequent research should develop practical methodologies for framework application. This includes creating step-by-step analytical protocols for applying 7ES to novel systems, decision trees for identifying element boundaries in ambiguous cases, quantitative metrics for measuring each element’s contribution to system function, visual representation standards for communicating 7ES analysis, and software tools enabling computational modeling of systems using 7ES structure.

Educational materials should be developed for teaching the framework across disciplines, including case studies demonstrating analysis process, common pitfalls and how to avoid them, and exercises for skill development.

7.5 Phase Five: Intervention Testing

The ultimate test of framework utility is whether it enables more effective system intervention and design. Research should compare intervention success rates between approaches informed by 7ES analysis and alternative methodologies. This phase should address questions including whether interventions targeting all seven elements prove more effective than those focusing on subset elements, whether the framework reveals non-obvious intervention points, and whether system designs explicitly incorporating all seven elements exhibit superior performance or resilience.

Application domains for intervention testing might include organizational redesign, policy development, technological system engineering, ecosystem management, and educational program design. Success metrics should be defined specific to each domain while maintaining cross-domain comparability where possible.

8. Expected Outcomes and Broader Impacts

This research program, if successfully executed, could yield outcomes with significant theoretical and practical implications.

8.1 Theoretical Contributions

Confirmation of 7ES universality would establish a standard analytical framework for systems theory, providing the field with a common vocabulary and structure currently lacking. This would facilitate cross-disciplinary communication and collaboration by enabling researchers to recognize structural similarities across domains despite surface differences. The recursive property would provide new insights into multi-scale phenomena and emergence by revealing how micro-level element interactions generate macro-level patterns.

Understanding which elements are universal and necessary versus contextual and optional would clarify fundamental questions about the nature of systems. This could inform philosophical debates about reductionism versus holism, mechanism versus teleology, and determinism versus agency.

8.2 Practical Applications

In engineering and design, a validated framework could guide more robust system architecture by ensuring all necessary functional elements receive attention during design phases. System diagnostics could be systematized by checking each element for dysfunction. Interdisciplinary teams could communicate more effectively using shared analytical structure.

In policy and organizational domains, the framework could improve intervention design by revealing how changes in one element ripple through others, identifying non-obvious leverage points for system transformation, and predicting unintended consequences through systematic element analysis. The racism case study demonstrates how understanding systemic persistence requires addressing all seven elements rather than isolated components.

In education, the framework could provide structure for teaching systems thinking across disciplines, enabling students to transfer analytical skills between domains and develop more integrative understanding of complex phenomena.

8.3 Limitations and Scope

Even if the framework proves universally applicable, its utility will vary by context. Some domains may benefit more from specialized frameworks tailored to specific phenomena. The framework describes system structure but does not automatically provide system-specific knowledge—domain expertise remains essential. Practical application requires methodological development beyond theoretical formulation.

The framework should be understood as a tool for analysis and communication rather than a complete theory of system behavior. It describes what systems are composed of but does not fully explain how they behave, why they emerge, or how they should be designed. Complementary theories addressing dynamics, evolution, and optimization remain necessary.

8.4 Philosophical and Metaphysical Implications

The universality and recursive nature of the 7ES Framework, if validated, extend beyond practical utility into profound philosophical territory, suggesting a fundamental re-interpretation of the nature of reality, knowledge, and existence.

8.4.1. From Descriptive Model to Ontological Claim:

The primary implication is a shift in the framework’s status. If the 7ES pattern is truly necessary and sufficient for all functional systems, it ceases to be merely a descriptive model we apply and becomes a fundamental architectural pattern we discover. This moves the 7ES from the epistemological realm (a tool for knowing) to the ontological realm (a structure of being). It posits that to exist as a coherent, persistent entity is to instantiate this specific, seven-fold pattern of functional relationships. The universe, at every scale of its functional organization, appears to be built from a recursive, fractal pattern of input, transformation, regulation, and connection.

8.4.2. A Universal “Syntax” for Reality:

The 7ES Framework provides a potential common functional language—a “syntax of system-ness”—that can bridge the disparate dialects of physics, biology, sociology, and philosophy. A biologist describing a cell, a physicist describing a quantum field, and an economist describing a market could all structure their understanding using the same seven functional primitives. This does not reduce one domain to another but reveals a deep structural homology, suggesting that the logic of functional organization is universal, even as the implementing substrates (fields, cells, individuals) are vastly different.

8.4.3. Implications for a “Theory of Everything” (TOE):

In fundamental physics, the quest for a TOE has largely focused on unifying the four fundamental forces. The 7ES Framework introduces a new, complementary constraint. A viable TOE must not only be mathematically consistent and unify forces at the Planck scale, but it must also explain the emergence of the 7ES pattern at all higher scales. The framework provides a “design requirement” for reality: any candidate TOE must be capable of generating a universe where this recursive, seven-element structure naturally arises in everything from atoms to galaxies. It shifts the question from “What are the fundamental fields and particles?” to “What fundamental rules give rise to a reality universally structured by 7ES?”

8.4.4. Redefining “Fundamentality”:

Physics has traditionally sought the “most fundamental” entity—the smallest, indivisible building block. The 7ES pattern suggests that a pattern of organization can be just as fundamental as a physical substrate. The “stuff” of the universe may not only be quantum fields or strings, but also the relational, functional principles that govern their organization. The pattern itself is a fundamental aspect of reality, recursively present at every level, implying that organization is not an emergent epiphenomenon but a primary feature of the cosmos.

8.4.5. The Nature of Causality and Interaction:

The recursive, fractal nature of 7ES reframes classical linear causality. Instead of simple cause-and-effect chains, the framework depicts a universe of nested, interacting processes. The “Output” of one system becomes the “Input” for another, not in a linear sequence, but within a dynamic, multi-scale network. This aligns with modern complex systems theory and offers a formal structure for understanding how micro-level interactions generate macro-level patterns (bottom-up causation) and how macro-level contexts constrain micro-level possibilities (top-down causation), all within a single, coherent functional architecture.

In conclusion, the 7ES Framework is more than a lens for analysis; it is a hypothesis about the deep structure of a coherent reality. Its validation would represent a significant step toward a truly unified understanding of the world, one where the logic of a living cell, a conscious mind, and a spinning galaxy are recognized as diverse expressions of a single, universal architectural principle.

9. Conclusion and Call for Collaboration

The 7ES Framework proposes that seven fundamental elements—Input, Output, Processing, Controls, Feedback, Interface, and Environment—constitute necessary and sufficient conditions for system function across all scales and domains. Preliminary evidence spanning from quantum field dynamics to cosmic structure formation suggests remarkable consistency in element identification. The framework’s recursive property enables multi-scale analysis while maintaining structural coherence.

However, preliminary evidence does not constitute proof. The framework’s universality claim requires rigorous testing across diverse domains, active attempts at falsification, comparison with alternative frameworks, and demonstration of practical utility beyond theoretical elegance. This white paper proposes a systematic research program to validate or falsify these claims through collaborative interdisciplinary investigation.

We seek collaborators across scientific disciplines willing to apply the framework within their domains of expertise, propose counterexamples and edge cases that challenge universality claims, contribute to theoretical analysis of necessity arguments, develop methodologies for practical application, and compare 7ES with established frameworks in their fields.

The framework’s value will be determined not by its elegance but by whether it enables insights and interventions unavailable through existing approaches. We welcome both supportive evidence and contradictory findings, as both advance understanding. If the framework proves universal, it provides systems theory with long-sought structural unity. If systematic testing reveals genuine counterexamples, this clarifies the framework’s scope and limitations, advancing the field through falsification.

Systems thinking has transformed numerous disciplines by revealing connections and patterns invisible to reductionist analysis. A validated universal framework for systems analysis could accelerate this transformation by providing common language, structure, and methodology across all domains where systems concepts apply. We invite the research community to join in determining whether the 7ES Framework delivers on this promise.

References

Foundational Systems Theory

Ackoff, R. L., & Emery, F. E. (1972). On Purposeful Systems. Aldine-Atherton.

Ashby, W. R. (1956). An Introduction to Cybernetics. Chapman & Hall.

Beer, S. (1972). Brain of the Firm: The Managerial Cybernetics of Organization. Allen Lane.Bertalanffy, L. von. (1968). General System Theory: Foundations, Development, Applications. George Braziller.

Checkland, P. (1981). Systems Thinking, Systems Practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Churchman, C. W. (1968). The Systems Approach. Dell Publishing.

Meadows, D. H. (2008). Thinking in Systems: A Primer. Chelsea Green Publishing.

Miller, J. G. (1978). Living Systems. McGraw-Hill.

Wiener, N. (1948). Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. MIT Press.

7ES Framework Development

Alden, C. (2025). 7ES (Element Structure) Framework for Systems Theory: A Universal Framework for the 21st Century. The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory. Retrieved from https://kosmosframework.substack.com/p/7es-element-structure-framework-for

Alden, C. (2025) Resolving Foundational Problems in Systems Theory:The 7ES Framework, The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory, Retrieved from, https://kosmosframework.substack.com/p/resolving-foundational-problems-in

Alden, C. (2025). Reconceptualizing Feedback: From Cybernetic Loops to Universal System States. The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory. Retrieved from https://kosmosframework.substack.com/p/reconceptualizing-feedback-from-cybernetic

Alden, C. (2025) The Fragmentation of Systems Thinking: How Institutional Forces Dismantled Bertalanffy’s Unified Vision, The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory, Retrieved from, https://github.com/KosmosFramework/7es_testing/blob/main/core_theory/The_Fragmentation_of_Systems_Thinking.pdf

Alden, C. (2025) The 7ES Calculus: A Universal Mathematical Framework for Complex Systems, The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory, Retrieved from, https://github.com/KosmosFramework/7es_testing/blob/main/core_theory/The_7ES_Calculus.pdf

Alden, C. (2025) Axiomatic Foundations of Universal Computation

First Principles of the 7ES framework, The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory, Retrieved from,

https://kosmosframework.substack.com/p/axiomatic-foundations-of-universal

Alden, C. (2025) Completing the Higgs Revolution: How Mass and Matter Dominance Enable Universal Computation, The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory, Retreived from,https://github.com/KosmosFramework/7es_testing/blob/main/core_theory/Completing_the_Higgs_Revolution.pdf

Information Theory and Communication

Shannon, C. E. (1948). A Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27(3), 379–423.

Atkinson, R. C., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1968). Human Memory: A Proposed System and its Control Processes. In The Psychology of Learning and Motivation (Vol. 2, pp. 89–195). Academic Press.

Cybernetics and Control Theory

Maruyama, M. (1963). The Second Cybernetics: Deviation-Amplifying Mutual Causal Processes. American Scientist, 51(2), 164–179.

Ogata, K. (2010). Modern Control Engineering (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Fractal Mathematics and Complexity

Hofstadter, D. R. (1979). Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books.

Mandelbrot, B. B. (1982). The Fractal Geometry of Nature. W.H. Freeman.

Holland, J. H. (1995). Hidden Order: How Adaptation Builds Complexity. Basic Books.

Autopoiesis and Biological Systems

Maturana, H. & Varela, F. (1980). Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living. D. Reidel.

Systems Engineering and Interface Design

Blanchard, B. S., & Fabrycky, W. J. (2010). Systems Engineering and Analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Reenskaug, T. (1979). Models – Views – Controllers. Xerox PARC.

Stair, R., & Reynolds, G. (2012). Principles of Information Systems (10th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Indigenous Knowledge Systems

Cajete, G. (2000). Native Science: Natural Laws of Interdependence. Clear Light.

Environmental and Social Systems

Emery, F. E., & Trist, E. L. (1960). Socio-technical systems. In C. W. Churchman & M. Verhulst (Eds.), Management Sciences, Models and Techniques (Vol. 2). Pergamon.

Scale and Complexity

West, G. (2017). Scale: The Universal Laws of Growth, Innovation, Sustainability, and the Pace of Life in Organisms, Cities, Economies, and Companies. Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Asymmetry and Complexity Theory

Alden, C. (2025). Alden Asymmetry Hypothesis: Asymmetry as the Fundamental Creative Principle in Complex Systems, The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory, Retrieved from https://kosmosframework.substack.com/p/the-alden-asymmetry-hypothesis

Arthur, W. B. (1994). Increasing Returns and Path Dependence in the Economy. University of Michigan Press.

Bak, P. (1987). Self-organized criticality. Physical Review A, 36(1), 364-374.

Barabási, A. L., & Albert, R. (1999). Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science, 286(5439), 509-512.

Granovetter, M. S. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78(6), 1360-1380.

Hinton, G. E. (2012). Improving neural networks by preventing co-adaptation of feature detectors. arXiv preprint arXiv:1207.0580.

Kuznets, S. (1955). Economic growth and income inequality. American Economic Review, 45(1), 1-28.

Maynard Smith, J. (1978). The Evolution of Sex. Cambridge University Press.

Prigogine, I. (1977). Self-Organization in Nonequilibrium Systems. Wiley.

Sakharov, A. D. (1967). Violation of CP invariance, C asymmetry, and baryon asymmetry of the universe. JETP Letters, 5(1), 24-27.

Tilman, D., & Downing, J. A. (1994). Biodiversity and stability in grasslands. Nature, 367(6461), 363-365.

Appendix A: Case Study Repository

Alden, C. (2025). The 7ES Framework: A Universal Architecture for Systems Analysis. The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory. (https://github.com/KosmosFramework/7es_testing)

Appendix B: Glossary of Terms

Alden, C. (2025). The 7ES Framework Glossary of Terms. The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory. (https://github.com/KosmosFramework/7es_testing/blob/main/educational_materials/7ES_Glossary_of_Terms.pdf)

Contact Information

Lead Researcher: Clinton Alden, The KOSMOS Institute of Systems Theory

Email: calden@thekosmosinstitute.org

Repository: https://github.com/KosmosFramework/7es_testing

Community Forum: The future home https://thekosmosinstitute.org/kist/

Acknowledgments

This work builds on decades of systems theory research from Ludwig von Bertalanffy, Norbert Wiener, W. Ross Ashby, and countless others who recognized the need for unified approaches to understanding complex systems. Special thanks to the enterprise clients and research collaborators who provided the real-world testing environments that validated and refined this framework.

Updates:

11-17-2025: Updated References, case study repository, glossary of terms, contact info (C.Alden)